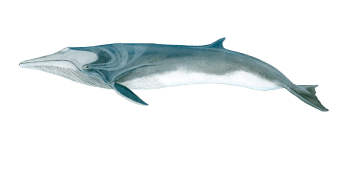

Fin whale

(Balaenoptera physalus)

The fin whale is the second largest living creature after the Blue whale. They are extremely agile, elegant swimmers and can reach speeds of up to 40 km/h which makes them one of the fastest of all the big whales and has granted them the nickname “Greyhounds of the ocean”.

Fin whales communicate using low frequencies in the infrasound range which can be heard by other fin whales as far as 850 km away.

They are shallow divers with a documented maximum of 230 m and can be very long-lived, with the oldest specimen on record – caught in Antarctica – being approx. 111 years old.

Fin whales are baleen whales and belong to the family of rorquals and use baleen plates as a filtering system for their prey (see Bryde’s whale portrait for further explanations on rorquals).

General information

Further names: Portuguese: Baleia-comum; English: Flathead

Size of adults: Females may grow up to 26m (larger than males)

Prey: Schooling fish, platonic crustaceans such as copepods and krill

Behaviour: Usually encountered alone or in small groups. When groups are seen in Madeira mating behaviour can also be observed.

Range: Globally distributed in deep tropical temperate and polar waters. Some populations migrate to warmer waters in lower latitudes in the winter and towards polar regions in the summer. Other Fin whale populations may stay in one place all year round, like those living in the Gulf of California and the Mediterranean.

Madeira: Encountered in late springbeginning of summer

Distinctive features: Probably the most elegant and slender of all larger whales with a high columnar spout and a large central ridge extending along their rostrum. Can easily be distinguished by the characteristic asymmetric colouring on their heads; the oral cavity, lower lip and baleen are white on the right side while on the left they are uniformly grey.

Taxonomy: Suborder: Mysticeti (Baleen whales); Family: Balaenopteridae (Rorquals)

Threats: Global populations of this species were heavily decimated due to intensive hunting in the last centuries. They are still hunted in Iceland, Greenland and Japan although populations worldwide are listed as threatened. Other threats to the species include collisions with vessels and entanglement in fishing nets.